… rather than have you work for your email.

Many of us will have encountered the problem of email taking over: I can receive several hundred emails a day at times. These come from a variety of sources:

- students

- immediate colleagues

- useful administration (related directly to my work, usually in teaching)

- other academics from beyond my institution

- useless administration (the endless nonsense from central university services that all academics have to endure)

- mailing lists

- other

It is a struggle to deal with this volume of email, especially since much of it is not urgent. Even if someone marks it as ‘urgent’ (as some university admin people like to do to everything they send), it is only urgent to them – and only rarely to me! I used to wade through them all, file some away, respond to others immediately, but somehow still ended up with hundreds waiting to be dealt with in some way in my inbox. J.P.E. Harper-Scott, a musicologist at Royal Holloway, has described a system to manage this volume of academic email, and at this juncture, you need to go and read his posting (click that link now: it’ll open in a new window/tab so you can easily come back to this page; don’t worry, I’ll wait for you…).

I wanted to add something to his system, because I do use it, but slightly differently. I am an ‘early adopter’ of email, and I have most important emails I have ever sent or received going back almost two decades (yes, I have good backup routines – that’s a topic for another day). I do use IMAP, but not to keep my email on a server. There are various reasons for this that I won’t go into here, but if you do the same, or – like me – don’t want to use GoogleMail, the instructions below may help you. My version of Harper-Scott’s system is slightly more cumbersome and has one notable disadvantage: because to-be-sent emails are connected to your email program, they will only be sent at pre-arranged times if your computer is on and your email program is running; if it is off, they will send when you next start your email program. This is not a problem for me – if it is not for you, keep reading.

My instructions are oriented around using a Mac – if you still use a Windows computer, it is probably much the same.

Your email client program

Firstly: you need a better email program than Apple’s Mail. A key function of Harper-Scott’s system is timing the sending of emails in advance, whether in the morning, or in the afternoon. Apple’s Mail is functional but basic – and can’t do that (at least, not without resorting to Automator, which loses some Mail functionality and is clunky beyond anything you want to put up with; I’ve tried it, believe me on this). There are two mainstream options for you that I am aware of: one is Microsoft’s email client, and the other is Thunderbird. I try to have as little Microsoft software on my computer as possible, so the former is out of the question for me, but Thunderbird is a great piece of software. Either will work.

Harper-Scott does not sort emails, relying instead on search facilities. I can’t quite let go of filing my emails, but I have minimised doing so, recognising that email client searches have improved enormously from my early days when filing was essential or nothing would ever be found again. My main filing system of ‘dealt with and just need to keep’ emails (and that obviously includes almost all emails I’ve sent) is organised by year, so this year’s folder looks like this:

2013

– Stirling (ALL my university emails)

– Einzelpersonen (ALL emails to or from non-Stirling individuals)

– Organisationen (ALL emails to or from non-Stirling organisations)

Yeah, I know, German – quirky, huh? When you have nearly 20 years of emails and the main folders have always had German names, you just stick with it…

Then I have a few other temporary subfolders in the Inbox (yes, these have English names…!) that I’ll describe below. Some of these are automatically filled, and others are manually dealt with:

Inbox

– internal

– Programme Director

– students

– print then file

– responses coming

– memos to read sometime

And this is how I use them: Thunderbird has simple to use filters that I have set to automatically move student email into the ‘students’ folder, and all other Stirling emails into the ‘internal’ folder (easy to do: undergraduate student addresses are in a uniform format so a filter for @students.stir.ac.uk catches them all; another similar filter deals with @stir.ac.uk which covers everyone else at the university). My actual inbox now contains only emails from outside the university – so as soon as I download my emails, they are automatically sorted into three main categories, making it easier to deal with them. Thunderbird helpfully marks folders with unread emails in two ways, in bold, and with the number of unread emails, for example:

Inbox (3)

– internal (12)

– Programme Director

– students (6)

I can now deal with these emails following Harper-Scott’s scheme.

But what is the Programme Director folder? This concerns emails that come to me in my administrative role as Religion Programme Director. I move ‘to-do’ emails in there and mark them as unread so that the folder name is bold and has a number. These are things that I know I need to come back to very shortly. If I think I will forget, I set myself an iCal reminder.

The other folders:

- print then file: I can’t print long documents at home, but if a PhD student sends me her latest chapters for comments, or I receive papers for a meeting, I need to print these. I put the email in here, and when I’m next in the office, I save and print the attachment, remove it from the email, and then file the email away.

- responses coming: often these will be emails I have sent to someone and for which I need their response. This is my reminder folder – if need be, I forward the email again. Once the query has been dealt with – or the question is no longer relevant! 🙂 – the email is filed away in the relevant 2013 folder.

- memos to read sometime: this is as inspiring as it sounds – these are mostly the tedious memos that go round the entire university dealing with subjects that I know are totally irrelevant to me, but that I feel I should read. Sometime. When I have a moment. Just now I have a couple in there from September 2012: maybe I can get away with not reading them at all – after all, the world hasn’t stopped just because I haven’t read yet another amendment to regulation 18.24.3.7, has it? Before you even start tutting: I am very aware that this folder’s sole purpose is to assuage guilt. I know I should read these terribly important emails because many of them come from people who see themselves as terribly important (coincidentally, they’re often people at the top of the university hierarchy), but eventually any residual guilt is gone and I can file them away unread. And the world tends to keep turning despite my dilatory approach to these emails…

Sending email at specified times

One of Harper-Scott’s key points concerns sending emails at specific times in the future. I am convinced that this is absolutely essential if you want to keep control of your email and not let it control you. Since adopting his system at the beginning of January I think I have sent two work emails (that concerned urgent pastoral matters for a student) outside the hours of 9-17h Monday-Friday, though I do, of course, write quite a number in the evenings and at the weekends. As he points out, keeping to a standard working day is not just important for you, it is a moral issue in relation to your colleagues and students. Read his post again if you need convincing of this (it’s ok, I’ll still be here when you’re finished…).

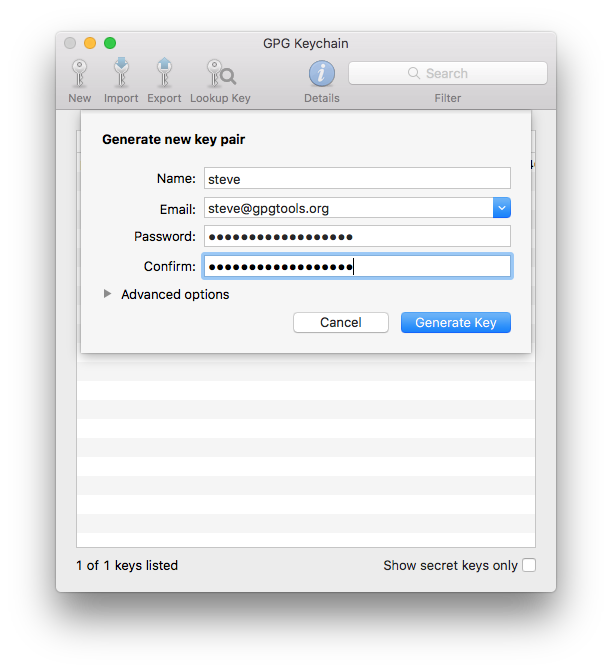

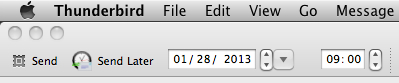

As I understand it, Microsoft email clients have a ‘send later’ function that you can use for this. The default Thunderbird ‘Send Later’ function is not as fully featured – it’s a leftover from days when we had dial-up modems and lets you write emails that are then sent as soon as you go back online. That’s obviously no use for delaying emails when most of us have broadband that is on all the time. But… one of the glories of Thunderbird is that you can easily install plug-ins to do all kinds of things, and there is a clever one with the imaginative name ‘Send Later‘. This allows you to specify exactly when an email should be sent, and it then stores it in your ‘drafts’ folder, ready to go. You can customise the ‘Write:’ new message toolbar with the relevant buttons (right click the toolbar if you haven’t done this before, and a menu will open – only American format dates, but time is 24h!). Mine now looks like this:

Thunderbird Send Later menu

And that email will now go at 9:00 tomorrow morning – simple… At the moment I have 24 emails in my drafts folder ready to go tomorrow morning, and one ready to go on 28. February concerning a document I was asked to complete and return – by 28. February.

Mobile telephones

One of my pre-reform email practices was to check and respond to emails in bed before getting up. I also did this at night when about to go to sleep. In bed! My day bookended by email. This is MADNESS. But I know many others who do this, so it is a collective madness. I would do this on my mobile telephone, and write replies to students and colleagues. Who did I think would benefit from getting my thoughts on any subject at 6:30 in the morning, or at 23:50 at night?! So I’ve stopped being so stupid, and now my telephone only has my work email turned on if I am away and need to use it to respond to email during the day. If you have an iphone or ipad etc., it is very easy to turn your email on and off, and no settings or emails are lost. This is how you do it: in the Settings menu, select Mail, Contacts, Calendars, and then select your work email. Then turn it off (go on, you can do it!):

Work email off!

Doesn’t that feel good? And if you have more than one work email (for example, I also co-manage an email account for a project we run in our department), do it for all of them, so that your main email settings screen looks like this:

ALL work email off!

Did you notice the time at the top of the screen? It’s Sunday evening, so I don’t want to see my work email! You’ll see that I’ve still left my personal email on – if my friends want to invite me to the cinema, I want to know about that.

I also have a basic folder system in operation on the IMAP server just for my mobile. There are four folders:

– Stirling

– Einzelpersonen

– Organisationen

– to-do

Anything that can be filed away into one of my three archive folders is filed away, and every now and then I will copy these to my main computer. The ‘to-do’ folder contains emails that I want out of my inbox because I’ve read them, but responding to them can wait until I get back to my main computer.

I hope this helps liberate you from your email, and allows you to use your email, rather than be beholden to it. Comments on how you find this system, or alternative implementations, are welcome.

Finally, if you want a stimulating read, I’m about half-way through Harper-Scott’s newest book, and I can highly recommend it!